|

|

|

Music man: Classic clavichords crafted in

Canton

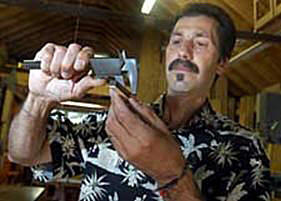

Charles Wolff measures a key for a clavichord he

is building in his shop in a late 19th century

carriage house next to his home. (LISA BUL/The

Patriot Ledger)

|

By ROBERT SEARS

The Patriot Ledger

CANTON - With its table saw, belt sander and other power

tools, Charles Wolff’s home workshop can be pretty

noisy, but the end result will be music to a demanding

musician’s ears.

The shop in a late 19th century carriage house next to

his home is dedicated to building one of the piano’s

early relatives, the clavichord.

It’s a somewhat unusual craft for a Nyack College piano

performance major whose woodworking experience was

limited to building a deck with his dad.

But Wolff made the switch from playing to building

keyboard instruments when he arrived in

Boston

in 1978 just in time for the blizzard and got an

internship with the noted builder of harpsichords, Carl

Fudge.

‘‘That was when I realized I wasn’t going to be a

concert pianist, and I thought, well, this is

interesting, I’ve always liked harpsichords,’’ he said.

Wolff honed his woodworking skills building harpsichords

and clavichords and do-it-yourself kits with Fudge for

10 years.

‘‘A Carl Fudge kit was a pretty big deal,’’ he said.

When Fudge retired, Wolff took over the business.

These days Wolff mainly builds clavichords. There have

been years he produced from 10 to 20 fully built and kit

versions, but he says the business is cyclical.

A large, completely built clavichord can cost $15,000 to

$20,000. Kits range from a few thousand to $6,000.

Wolff’s customers include professional musicians,

amateur players, and music schools.

‘‘There are a lot of amateur players, some great ones,’’

he said.

For a time, his clavichords were exact copies of

original 18th century instruments, but these days he’s

tweaking the designs to his own standards. ‘‘I thought I

needed a change,’’ he said.

His clavichords are not radically different, and changes

are mostly invisible to the casual observer. They can

involve the keyboards, the positioning of the bridge and

the way the cabinets are braced, for example.

‘‘That’s heresy to some people, but I’ve built so many,

and you learn from what you’ve done. The older builders

did the same thing,’’ Wolff said.

‘‘The clavichord is basically a very simple instrument.

The main components are the keys, the strings, the case,

which contains the soundboard and the bridge. The bridge

and soundboard are probably the most important parts,’’

he said.

Wolff likes Sitka spruce for soundboards, both for its

color and ‘‘great tonal qualities.’’ Bridges are usually

made of beech but can be maple. Structural members are

mostly pine or poplar.

The case of his most recent clavichord is cherry wood

with inlaid mother of pearl and ebony. The keyboard is

basswood. The black keys are ebony; the white keys are

bone, since the use of ivory is outlawed in the United

Sates.

Wolff strings his instruments with special hand-drawn

wires from

England. ‘‘It’s beautiful stuff. The sound is just

unbelievable,’’ he said.

A ‘‘good touch’’ is a hallmark of a well-built

clavichord. Its mechanism should be smooth and quiet

without rattles.

‘‘A clavichord with good touch is sensitive, reacts

quick, returns really fast - you can play really fast on

these things. You want something that really feels good

that doesn’t get in the way of your playing,’’ Wolff

said.

‘‘What’s great about the clavichord is that it gives you

direct contact with the strings. It’s sort of like a

guitar, you can bend the string and get different sounds

that way, and it’s a really sensitive instrument. It

really teaches you to use proper technique. You can’t

play sloppy; it just won’t sound right,’’ Wolff said.

He has built several of the rarest type clavichords that

are played with foot pedals. They are played in

conjunction with one or two hand-played clavichords,

kind of like an organ.

‘‘I’ve probably built more than anyone in the U.S. -

four of them,’’ Wolff said.

‘‘The last one I built was my own design. I took a

historic model and turned it inside out and around so

that it would work the way I wanted it to work,’’ Wolff

said.

Recently Wolff has been designing changes he believes

will greatly improve upon the clavichords built by the

old masters.

‘‘I want to make one that will be different in response

and touch. It will look a little different because I’ll

have to move things around,’’ he said.

‘‘I’ve been brainstorming, throwing things on paper. It

looks good. It looks easy, then you start doing the math

and you realize why clavichords have looked the way they

do for 300 years,’’ he said.

Copyright 2007 The Patriot Ledger

Saturday, September 29, 2007

|

|

|